February 10, 2021

Australia’s gold industry stamped out mercury pollution — now it's coal's turn

Coal-fired power plants are now Australia’s largest controllable source of mercury emissions, releasing between two and four tonnes of mercury every year

Mercury is a nasty toxin that harms humans and ecosystems. Most human exposure comes from eating contaminated fish and other seafood. But how does mercury enter the Australian environment in the first place?

Our recent research dug into official data and past research to answer this question.

In some rare good news for the environment, it turns out one Australian industry – gold production – has brought mercury emissions down to almost zero. But more can be done about mercury emitted from coal-fired power stations.

Australia is one of the few developed countries yet to ratify the United Nations’ Minamata Convention on Mercury, which aims to reduce mercury in the environment. But once we deal with emissions from coal burning, we’ll be closer than ever to addressing the problem.

Where does mercury pollution come from?

Mercury is a heavy metal that cycles between the atmosphere, ocean and land. It occurs naturally but can be toxic to humans and wildlife.

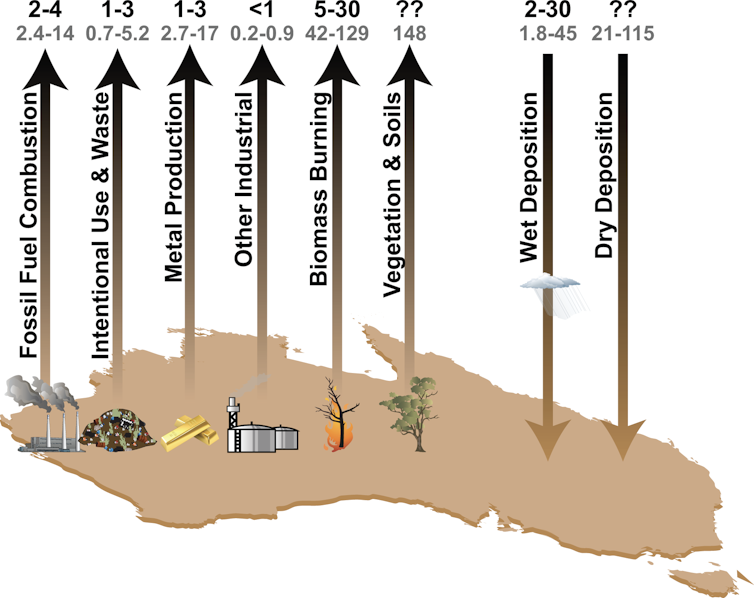

Most human-caused mercury emissions come from the burning of fossil fuels and the mining and production of gold and other metals.

What’s more, items such as light bulbs and thermometers dumped in landfill can release mercury 30-50 years later.

Once in the air, mercury can float around for months, crossing oceans and continents to end up back on the ground, far from where it was emitted.

It’s eventually taken up by soils, water and plants, then slowly released back to the atmosphere.

A success story

Estimates vary on the exact amount of mercury that Australian activities release to the air. Studies we reviewed put the figure at anywhere between 8 and 30 tonnes each year.

Our analysis shows the figure is likely at the low end of that range – largely due to a single success story.

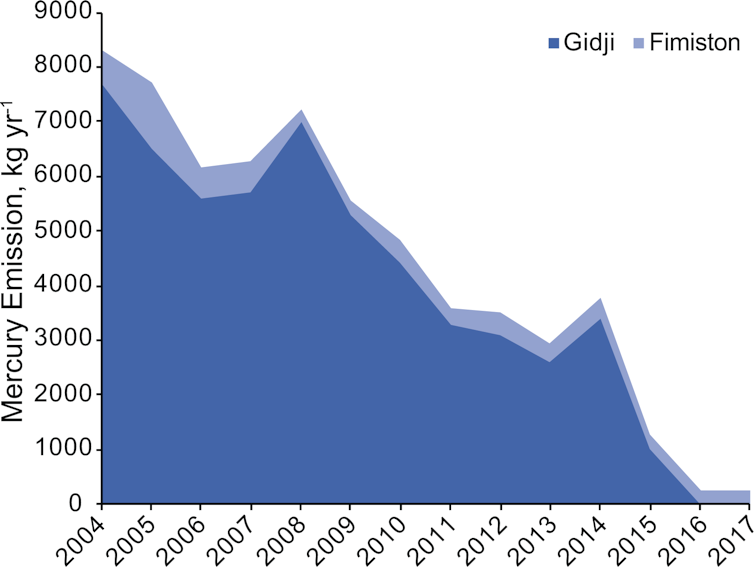

In 2006, a gold production facility in Kalgoorlie was thought to cause half of Australia’s industrial mercury emissions. The massive operation includes the Fimiston Open Pit, or “Super Pit”, purportedly so large it can be seen from space.

Gold ore naturally contains mercury. To extract the gold, the ore is typically roasted at temperatures of up to 600℃. During this process, the mercury escapes into the atmosphere. Most mercury pollution from Australia’s gold industry came from a single roaster at the Kalgoorlie site.

But over one decade, mercury emissions from the operation dropped from more than 8 tonnes to just 250 kilograms. This was largely due to a technology upgrade in 2015, when the roaster was replaced by a grinding process.

This success means coal-fired power plants are now Australia’s largest controllable source of mercury emissions. They emit between two and four tonnes of mercury every year (along with other air pollutants).

Other sources of mercury emissions

Other natural and human activities release mercury into the air. They include:

Bushfires: Mercury is usually released to the environment over decades. But the process can be much more rapid if the vegetation burns in a bushfire.

Our research found most estimates of bushfire emissions fall between 4 and 40 tonnes each year. But this work relied on measurements from overseas. New measurements from Australian ecosystems suggests past estimates are probably too high – possibly due to lower mercury concentrations in some Australian vegetation.

Soils and unburnt vegtation: Only one study has calculated the mercury released from Australian soils and unburnt vegetation, which it put at a whopping 74 to 222 tonnes per year.

When that research was published in 2012, there were no Australian data to test the model behind these numbers. We still don’t have many measurements, but most data we do have show Australian soils and vegetation take up about as much mercury as they release.

The one exception is “enriched” soils, which contain more mercury than other soils. This is because they are located over natural mineral belts and at former mining sites. At one location in northern New South Wales, enriched soils emitted more than 100 times as much mercury as nearby unenriched soils.

Mercury from elsewhere: Mercury released by other countries can travel to Australia in the air. The levels are tough to quantify, but we are currently using models to produce an estimate.

It’s time to act

Even with our new, lower estimates, Australia’s per capita mercury emissions remain higher than the global average, likely due to our reliance on coal burning. Technology can lower these emissions.

Some mercury emitted by power plants isn’t in the air for long before it falls to Earth. This can harm nearby people and ecosystems.

The federal government recently banned mercury-containing pesticides used in sugar cane farming. With gold production also taken care of, reducing mercury emissions from power plants is the logical next step.

It’s also time for Australia to formally commit to the Minamata Convention. Once we ratify the deal, we’ll be bound to control mercury emissions under international law – and that’s good for humans and wildlife everywhere.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.