September 13, 2021

Photos from the field: why losing these tiny, loyal fish to climate change spells disaster for coral

Environmental scientists see flora, fauna and phenomena the rest of us rarely do

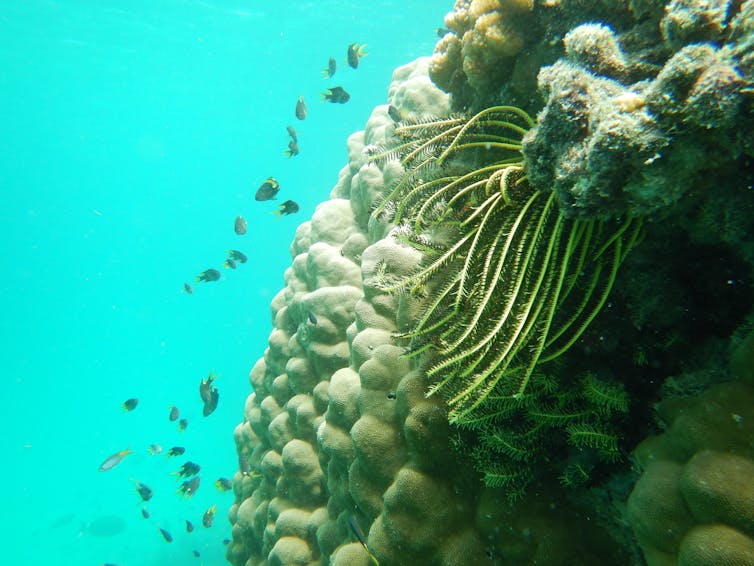

If you’ve ever dived on a coral reef, you may have peeked into a staghorn coral and seen small fish whizzing through its branches. But few realise that these small fish, such as tiny goby fish, play a crucial role in helping corals weather the storm of climate change.

But alarmingly, our new research found gobies decline far more than corals do after multiple cyclones and heatwaves. This is concerning because such small fish — less than 5 centimetres in length — are critical to coral and reef health.

Unfortunately, the number of cyclones and heatwaves is on the rise. These disasters have begun to occur back-to-back, leaving no time for marine life to recover.

With the recent push by UNESCO to list the Great Barrier Reef as “in danger”, the world is currently on edge about the status of coral reefs. We’re at a critical stage to take all the necessary measures to save coral reefs worldwide, and we must broaden our focus to understand how the important relationships between corals and fish are affected.

Goby fish: the snack-sized friends of coral

In all environments, organisms can form relationships where they work together to improve each other’s health. This is called a mutual symbiosis, like a you-scratch-my-back principle.

In coral reefs, other examples of mutual symbioses include invisible zooxanthellae algae living within coral tissue, small cleaner fish removing parasites from big fish, and eels and groupers hunting together.

Gobies that live in corals are small, snack-sized fish that rarely venture beyond the prickly borders of their protective coral homes. The Great Barrier Reef is home to more than 20 species of coral gobies, which live in more than 30 species of staghorn corals.

In return for the coral’s protection, the gobies pluck off harmful algae growing on coral branches, produce a toxin to deter potential coral-eating fish, and reduce heat stress by swimming around the coral and stopping stagnant water build up.

Even if their corals become stressed and bleached, they remain steadfast within the coral, helping it to survive. Without their full-time cleaning staff, corals would be more susceptible when threatened with climate change.

Unfortunately, just like Nemos (clownfish) living inside anemones, climate change threatens the mutual symbioses between gobies and corals.

Coral gobies in decline

While SCUBA diving, we surveyed corals and their goby friends over a four-year period (2014-17) of near-continuous devastation at Lizard Island, on the Great Barrier Reef. Over this time, two category 4 cyclones and two prolonged heatwaves wreaked havoc on this world-renowned reef.

What we saw was alarming. After the two cyclones, the 13 goby species (genus Gobiodon) and 28 coral species (genus Acropora) we surveyed declined substantially.

But after the two heatwaves, gobies suddenly fared even worse than corals. While some coral species persisted better than others, 78% no longer housed gobies.

Importantly, every single goby species either declined, or worse, completely disappeared. The few gobies we found were living alone, which is especially concerning because gobies breed in monogamous pairs, much like most humans do.

Without urgent action, the outlook is bleak

More and more studies are showing reef fish behave differently in warmer and more acidic water.

Warmer water is even changing reef fish on a genetic level. Fish are struggling to reproduce, to recognise what is essential habitat, and to detect predators. Research has shown clownfish, for example, could not tell predatory fish (rockcods and dottybacks) from non-predators (surgeonfishes and rabbitfishes) when exposed to more acidic seawater.

The bigger picture looks bleak. Corals are likely to become increasingly vulnerable if their symbiotic gobies and other inhabitants continue to decline. This could lead to further disruptions in the reef ecosystem because mutual symbioses are important for ecosystem stability.

We need to broaden our focus to understand how animal interactions like these are being affected in these trying times. This is an emerging field of study that needs more research in the face of climate change.

On a global scale, multiple disturbances from cyclones and heatwaves are becoming the norm. We need to tackle the problem from multiple angles. For example, we must meet net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and stop soil erosion and agricultural runoff from flowing into the sea.

If we do not act now, gobies and their coral hosts may become a distant memory in this warming climate.![]()

Catheline Y.M. Froehlich, PhD Fellow, University of Wollongong; Marian Wong, Senior Lecturer, University of Wollongong, and O. Selma Klanten, Research Scientist, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.