Next, we incorporate these downscaled samples in GLM inference. At the core of our framework is a spatial Berkson-error model. Berkson error happens when data on explanatory variables are not collected or are measured with error, and the explanatory variable is replaced with a smooth predictor (e.g., Carroll et al., 2006). In this model, an explanatory variable at fine resolution, say $X^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ on the BAU located at $s_i$, is decomposed into two components:

$$X^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)={\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)+\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right),$$

where ${\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ is the smooth predictor (here the mean of the downscaled samples at the $i$-th BAU), and $\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ represents a downscaling error. Importantly, the downscaling error is spatially correlated, as a result of the natural spatial structure (spatial range $\psi_0$) and heterogeneity (spatial variance $\sigma_0^2$) of environmental processes; see Zheng et al. (2025a).

Recall that a GLM with explanatory variable ${X}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ can be written as, for $i=1, \dots, N\thinspace$,

$$\begin{aligned}

\left[Z^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\thinspace|\thinspace Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right] &=EF\left(Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right),\\

g\left(Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right) &=\beta_0+\beta_1X^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right),\\

\end{aligned}$$

where for the BAU at $s_i\left(i=1, \cdots, N\right)$, $Z^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ is the response data; $\left[Z^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\thinspace|\thinspace Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right]$ denotes the conditional distribution of $Z^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ given $Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$; EF is a distribution that belongs to an exponential family such that $E\left(Z^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\thinspace|\thinspace Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right)=Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$; and $g\left(\cdot\right)$ is an invertible link function, with unknown regression parameters $\beta_0$ and $\beta_1$ and a single (climate) explanatory variable $X^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$. Of particular interest is the strength of dependence $\beta_1$.

To account for the downscaling uncertainty properly, both components, ${\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ and $\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$, are included in the GLM as follows:

\begin{aligned}

g\left(Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right)&=\beta_0+\beta_1X^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\\

&=\beta_0+\beta_1\left({\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)+\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right)\\

&=\beta_0+\beta_1{\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)+\delta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right),\\&\\

\end{aligned}

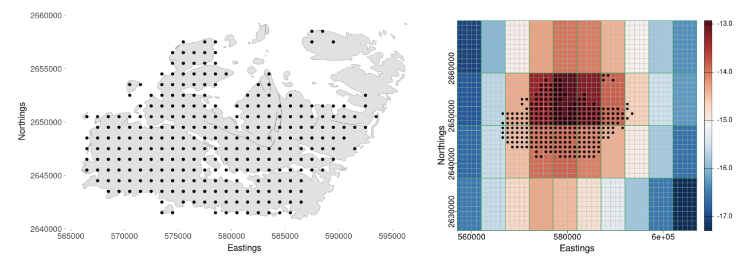

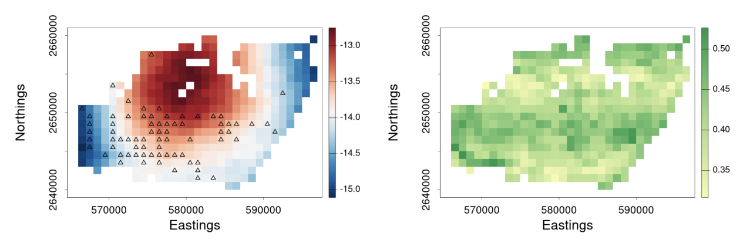

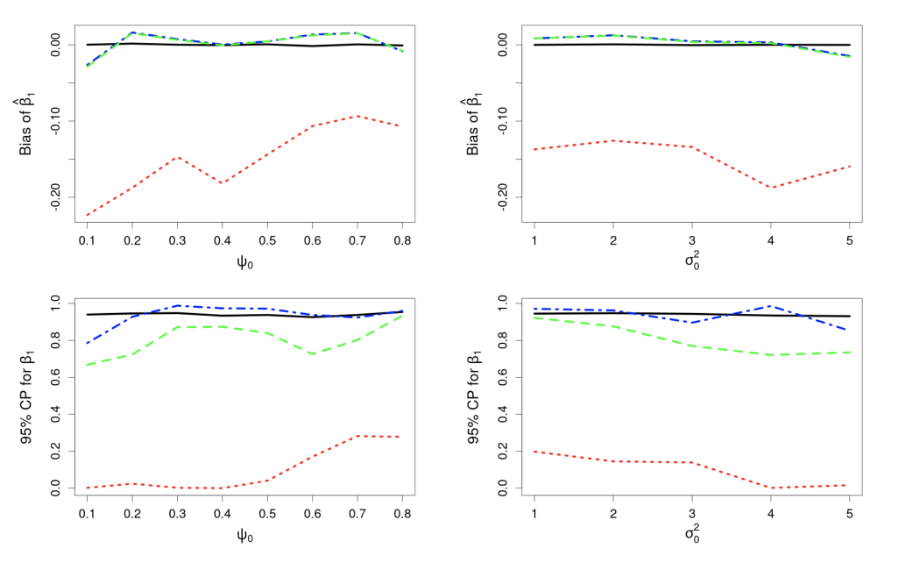

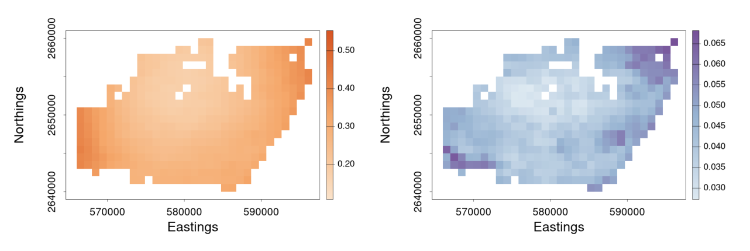

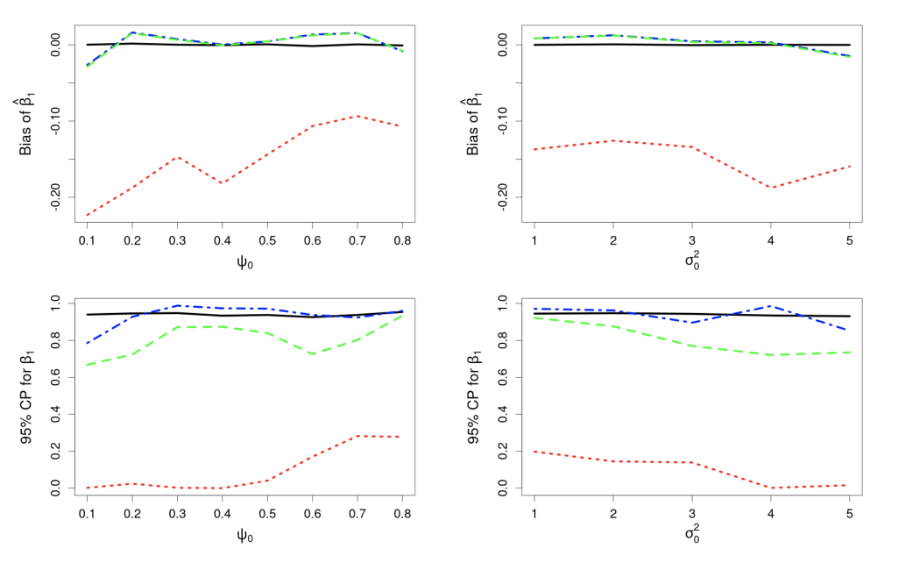

where the uncertainty in the GLM due to downscaling is incorporated through the component $\delta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\equiv\beta_1\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$, which is seen to be the downscaling error $\eta^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ scaled by $\beta_1$. The simulation results given in Figure 4 show why including the downscaling error matters: Inference using CORGI (colour blue) is valid compared to the commonly used ‘plug-in’ approach (colour green), which simply substitutes ${\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ without accounting for the error (i.e., $g\left(Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right)=\beta_0+\beta_1{\hat{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$). Another approach called ‘ensemble’ (colour red) shown in Figure 4, directly includes downscaled samples without using the Berkson-error decomposition (i.e., $g\left(Y^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)\right)=\beta_0+\beta_1{\widetilde{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$, where ${\widetilde{X}}^{\left(f\right)}\left(s_i\right)$ is a generic downscaled sample). While the ‘ensemble’ approach seems intuitively appealing, it can lead to biased and invalid inferences. Recall that CORGI incorporates downscaling uncertainty in GLM inference. Figure 5 demonstrates Monte Carlo downscaled samples of $\mathbf{X}^{(f)} = (\mathit{X}^{(f)}{(s_1)}, \dots, \mathit{X}^{(f)}{(s_N)})^{\top}$ and the associated Monte Carlo samples of $\mathbf{Y}^{(f)} = (\mathit{Y}^{(f)}{(s_1)}, \dots, \mathit{Y}^{(f)}{(s_N)})^{\top}$.

Figure 4: Comparison of CORGI (blue) to other methods, ‘plug-in’ (green) and ‘ensemble’ (red), where the black line represents the target quantity (Bias = 0; CP = 0.95). Top row: Bias of estimate ${\hat{\beta}}_1$ against spatial range $\psi_0$ and spatial variance $\sigma_0^2$, respectively. Target Bias = 0. Bottom row: Coverage probability (CP) for $\beta_1$ against spatial range $\psi_0$ and spatial variance $\sigma_0^2$, respectively. Target CP = 0.95.

Figure 5: (Left panel) 100 Monte Carlo samples of $\mathbf{X}^{(f)}$; (Right panel) 100 Monte Carlo samples of $\mathbf{Y}^{(f)}$ under CORGI, where $\textbf{Y}^{\left(f\right)}=g^{-1}\left(\beta_0\textbf{1}+\beta_1\hat{\textbf{X}}^{\left(f\right)}+\boldsymbol{\delta}^{\left(f\right)}\right)$.