January 11, 2018

Scientists find earliest evidence of humans altering the environment

Study reveals that introduction of agriculture 3,500 years ago profoundly changed ecosystems

In a paper published in Nature Scientific Reports, researchers from the University of Wollongong’s (UOW) School of Earth and Environmental Sciences have provided the earliest unequivocal evidence in the geological record of a profound human effect on the environment.

The paper shows how soils have responded to natural climate variation over the past 12,000 years, and that human activity around 3,500 years ago disturbed this natural equilibrium.

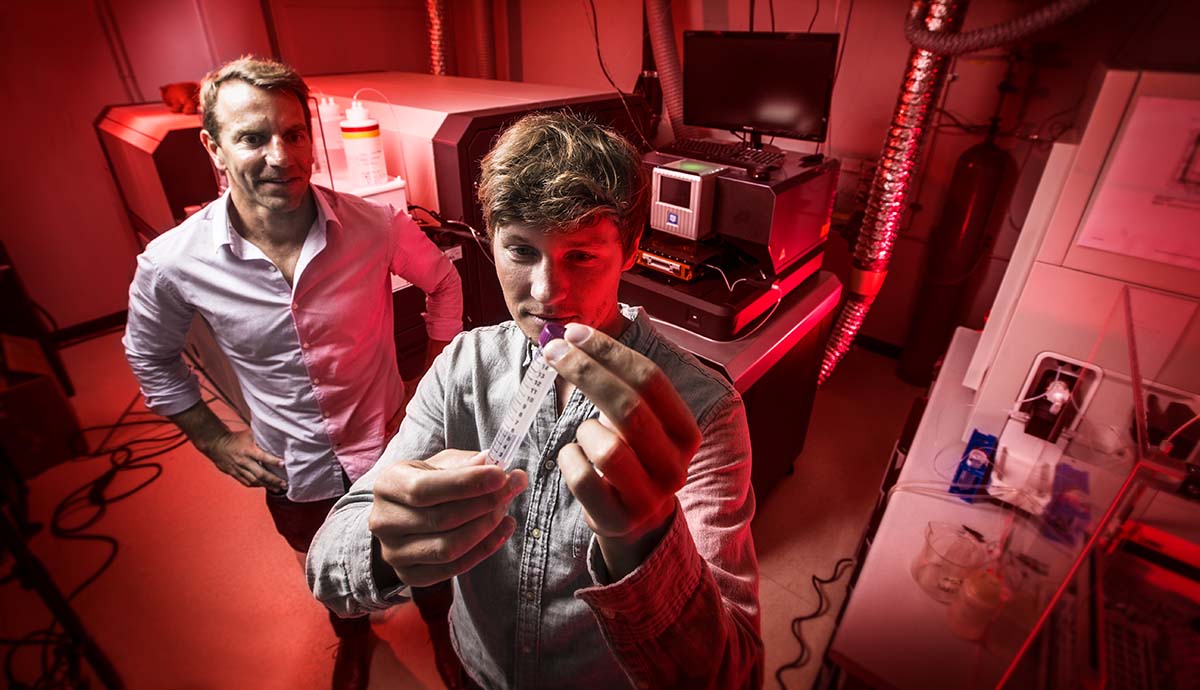

The paper’s lead author, UOW PhD student Mr Leo Rothacker, said soils are key components of ecosystems and vital to human societies, making it important to understand how they evolve through time.

“Soils are one of the most important components of the Earth’s ecosystems. In order to sustain future soil resources, we must understand how soils respond to changes in climate and human land-use,” he said.

“Previous studies have linked the downfall of civilisations to soil diminishment via accelerated erosion, which resulted in poor agricultural yields and might have caused wide-spread starvation.

“Our study provides the first evidence that this is exactly what happened in ancient Greece/Macedonia 3,200 years ago. Our data indicates that the human impact via agricultural practices was so dramatic that soils were completely stripped from the landscape.

“This could have contributed to the establishment of the Greek ‘Dark Ages’, a time where population declined rapidly, agriculture suffered, the metallurgy of bronze and the ability to write were forgotten.”

The researchers studied sediments deposited in Lake Dojran in Macedonia and Greece to see how natural climate change and human activity had affected soils in the region over the past 12,300 years.

The sedimentary record revealed an unprecedented erosion event associated with the development of agriculture in the region between 3,500 and 3,100 years ago, indicating a transition from a natural to an anthropogenic landscape.

“Lakes are excellent archives to unravel the environmental variability in the geological past,” co-author Dr Alexander Francke said.

“In particular relatively small and shallow lakes (such as Dojran) are highly sensitive to environmental variability.

“Lake Dojran further benefits from the fact its catchment area is small, which provides a more direct connection between hillslope erosion and sediment deposition in the basin, and the local paleoclimatic conditions have already been extensively studied. This allows us to directly link erosion to climate and thus to unravel natural and human causes of accelerated hillslope erosion.

“Our evidences for dramatic erosion 3,200 years ago coincides with the first occurrence of cultivate plant taxa in the pollen record. This supports that humans removed trees at that time, to replace them by cultivated plants.

“Climate variability cannot be invoked to explain these changes since no significant change in climatic conditions is known for this time interval, and we show that before 3,200 years ago, the response of soil erosion and development to climate change is very different to that what is observed at 3,200 years.”

Co-author and team leader Associate Professor Anthony Dosseto said the study provides evidence that the Anthropocene, a proposed geological period dating from the commencement of significant human impact on the Earth's geology and ecosystems, began much earlier than its most commonly given starting point at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

“Several propositions have been made for the onset of the Anthropocene,” Professor Dosseto said. “Some have proposed that it started as early as the emergence of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution (ca 12,000 years ago), however, supporting observations are scarce.

“Our study shows clear evidences that as early as 3,200 years ago humans modified their landscape so deeply that it is recorded in the lake sediment archives. This supports that the Anthropocene – and thus a deep human impact on the environment – started as early as a few thousand years ago.”

The research team is undertaking a similar study at nearby Lake Ohrid, with early results showing similar patterns to those seen at Lake Dojran. Professor Dosseto said the team would also study other sites around the world.

“We are applying the novel tools presented in our study to various locations around the world, including Australia and New Zealand. This will provide unprecedented insights on how soil resources respond to climate change, and how early humans have impacted their environment,” Professor Dosseto said.

“Impact of climate change and human activity on soil landscapes over the past 12,300 years” by Leo Rothacker, Anthony Dosseto, Alexander Francke, Allan R. Chivas, Nathalie Vigier, Anna M. Kotarba-Morley and Davide Menozzi is published in Nature Scientific Report on 10 January 2018. The research was funded by ARC Discovery Project DP140100354.