June 9, 2015

SBS Radio should look to its past to nurture its future

The plurality of cultures at SBS Radio, and broadcasters’ deep connections to their communities in Australia and overseas, will enable it to continue to make a remarkable and valuable contribution to Australian society

For some 40 years, SBS Radio broadcasters have delivered homeland news to migrants, mediated Australian politics and culture, and provided a platform for Australia’s 200 or so ethnic communities. The most multicultural broadcaster in the world, going to air in 74 languages, its promulgation of social cohesion in an era of heightened ethnic and religious tensions provides lessons not just for Australia, but for any multicultural society.

Not that it started out with such lofty notions.

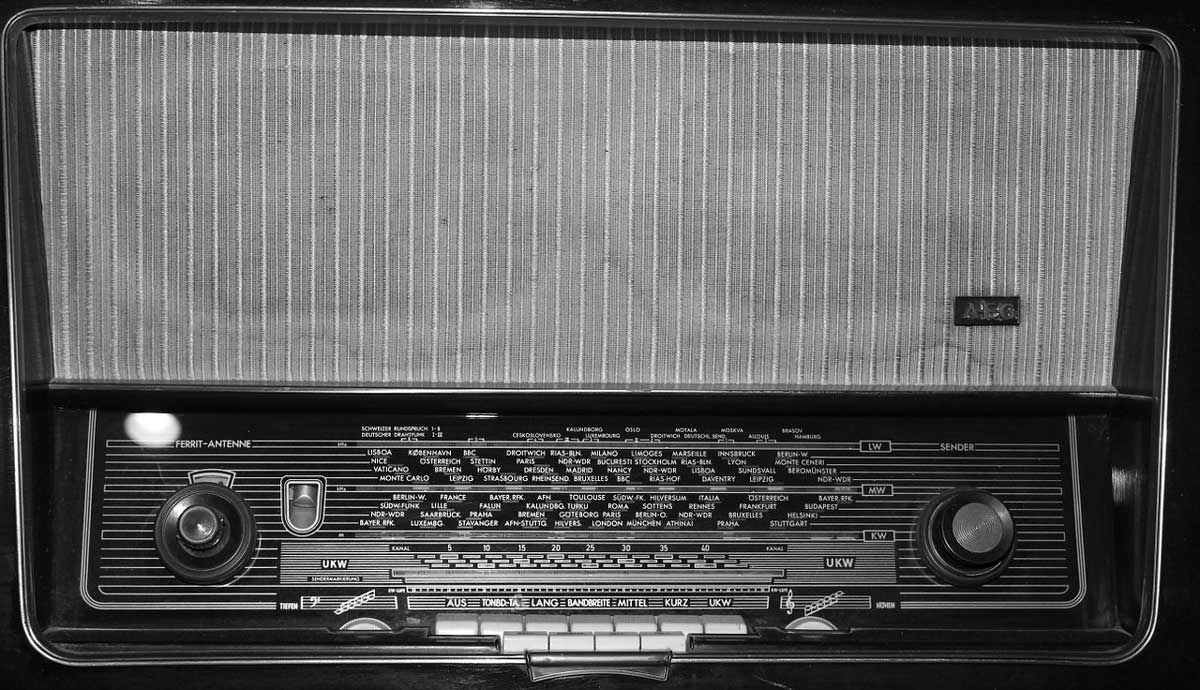

Its precursor, Radio Ethnic Australia, was launched as 2EA in Sydney on June 9, 1975 – 40 years ago today, in fact – and on 3EA in Melbourne shortly after, as a way to provide information to migrant groups on government initiatives such as Medicare.

In a pre-internet era, it was a thrill for migrants to hear their own language on Australian airwaves. As The SBS Story, a 2008 book on the broadcaster, recounts, a Turkish truckdriver driving down Parramatta Road, Sydney, was so elated on hearing the first Turkish broadcast, he got out and danced, causing a traffic jam.

Starting with eight, mostly European, languages, SBS Radio’s evolving language groups reflect the changing demographics of Australian society.

It remains hugely important in connecting new communities rendered fragile by war: for instance the Afghani community, whose Pashto broadcaster, Abdullah Alikhil, fled to Australia in 2012, following threats from the Taliban.

Besides providing vital information on homeland politics for recent migrants whose English is still poor, SBS Radio’s national footprint allows Alikhil to build community identity. In an interview for this article he said:

I attend a lot of community gatherings and broadcast them back, giving a voice to the community firstly, but also unifying the Pashto community from around Australia.

Broadcasters or journalists?

Early SBS “broadcaster/journalists” (BJs) were often popular community figures rather than professional journalists. The current author’s (McHugh’s) Sydney trainee group in the mid-‘90s included a Danish plumber, a Gujurati vet, a Croatian air stewardess and a Rwandan refugee.

As Training Manager in Melbourne, this article’s contributor (Hocking) conducted a skills audit of staff. She found “highly qualified actors, theatre directors, musicians, writers, film makers, translators, cross cultural mediators, artists".

Their cultural backgrounds did not always conform to Australian journalistic norms. McHugh recalls a baffled Russian emigrant in the 1990s who expostulated: “But we haven’t told the listeners what to think!” Others openly intruded their politics: one BJ solicited donations for a military campaign in his homeland for months before being detected.

From the 1990s, SBS Radio ramped up its BJ training. Programs were translated and audited at random, to ensure they complied with SBS codes.

Broadcasters reporting on such critical events as the Balkan War had to tread a delicate path. A BJ from one side of a conflict could be stationed at a desk metres from one reporting the opposite perspective; listeners also had strong and diverse opinions; yet BJs were supposed to maintain editorial balance.

Some groups did not always toe the line. Vietnamese, for instance, was openly pro-South Vietnam. But collaborations also developed. Hocking guided Turkish broadcaster Bulent Ibrahim and Greek broadcaster Yugenia Moraitis in their first, award-winning attempt at radio documentary-making – on the sensitive topic of how Australian Greek and Turkish migrants viewed the Greco-Turkish war.

Shifting demographics and digital innovation

Italian, Greek, Arabic, Vietnamese, Cantonese and Mandarin remain the dominant communities, but the Arabic language program now serves 22 ethnicities. One of its producers, Ghassan Nakhoul, won SBS Radio’s first Walkley Award, for a documentary, in Arabic, The Five Mysteries of Siev X.

Other broadcasters have delved into topics such as the Italian migrant experience, the history of Fiji’s indentured Indian labourers and the Srebenica massacre.

Audience demographics are continually monitored. In 2006, four languages (Irish Gaelic, Scots Gaelic, Welsh and Byelorussian) were dropped to make way for newer communities: Amharic (Ethiopian), Nepalese, Malay and Somali. In 2013, a restructure increased airtime for Punjabi and Hindi, and introduced six new languages: Malayalam, Hmong, Pashto from Asia, and Dinka, Swahili and Tigrinya from Ethiopia/Eritrea.

The Dinka program provides reliable information for the war-torn Sudanese community. Its broadcaster, David Chiengkou, does not relay second-hand stories. Talking to us for this article, he said:

I am very persistent. So when we want to talk to the government of South Sudan we have a direct telephone to the office of the Minister of Information. When we want to talk to the army we have the direct telephone of the army spokesperson. […] We have access also to the top leadership of […] the rebels.

Technology has wrought other changes. Apps, online delivery and smartphones have attracted a new CALD (Culturally and Linguistically Diverse) youth audience. Online music shows showcase popular trends from Bhangra, Bollywood, Desi, the Middle East and Asia; Pop Asia is the number-one digital-only radio station based on Facebook in Australia.

SBS Radio is now a less separate entity. Radio and social media are integrated with SBS TV, to support breakthrough programs such as Go Back to Where you Came From (2011), giving enormous penetration of non-English-speaking communities.

This pan-approach has been applied to topics such as Anzac Day, eliciting war stories from Sikh, Italian and Polish listeners, to give a more nuanced view of national milestones.

But this challenge to a monolithic “Australian” history suffered a setback with the recent sacking of SBS reporter Scott McIntyre for posting on social media comments that rejected the glorification of Anzac Day.

Social cohesion in the ‘terror’ era

In an online age, when citizens of a democracy such as Australia can freely search out cultural communities and track the news in their homeland, it could be argued that the funding of SBS Radio is a waste of public money.

But with extremists such as IS cleverly using social media to promulgate propaganda and recruit followers, the need for a public broadcasting sphere that adheres to principles designed to uphold a civil society is clearer than ever.

Its aim should be to elevate rather than to degrade the public, to echo sentiments extolling freedom of the press expressed in the aftermath of the second world war (Hutchins Commission on Freedom of the Press, 1947).

If the government is serious about tackling homegrown jihadism, as its recent budget allocation of A$450 million to national security operations suggests, it should be channelling more, not less, resources to SBS: the budget saw a cut of A$2million, from A$285 to A$283 million annually.

SBS should also look to its own history to nurture its strengths. Its increasingly corporate model aligns with mainstream media organisations, but SBS Radio needs to retain its community advocacy role.

It is the plurality of cultures at SBS Radio, and broadcasters’ deep connections to their communities in Australia and overseas, that will enable it to continue to make a remarkable and valuable contribution to Australian society.

![]()

By Siobhan McHugh, Senior Lecturer, Journalism

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.