September 11, 2014

Weakness in malaria parasite fats could see new treatments

A new study has revealed a weak spot in the complex life cycle of malaria, which could be exploited to prevent the spread of the deadly disease.

The study found female malaria parasites put on fat differently to male ones.

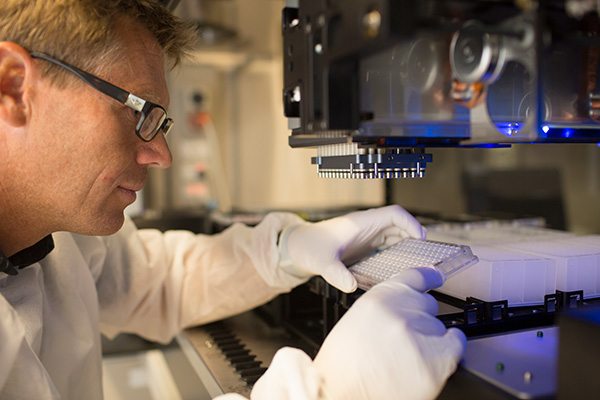

Associate Professor Todd Mitchell (pictured above), an ARC Future Fellow who holds dual roles at UOW's School of Medicine and the Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute, co-authored the study, which was recently published in Nature Communications. He said the study exposes potential new ways to combat malaria.

"One of the problems with current malaria treatments is that while they treat the symptoms of the infected individual, many of the drugs can increase transmission,” he said.

“This finding provides us with a possible target to eliminate transmission. This would be a big step towards eradicating the disease.”

More than half a million people die of malaria every year and 40 per cent of the world’s population is at risk of contracting the disease.

The spread of malaria by mosquitoes is a surprisingly inefficient process. Nearly all the parasites ingested by a mosquito in a meal of infected red blood cells are killed by the mosquito’s digestive processes, and so are not passed on to other humans.

A tiny percentage survive – the one in 10,000 that have developed into a more sophisticated form of the malaria parasite, called gametocytes, which resist digestion and then breed inside the mosquito.

Co-author Associate Professor Alexander Maier from the Australian National University’s Research School of Biology said that we are loosing our weapons against the disease.

“Malaria parasites show resistance to all current anti-malarial drugs…But by studying lipid molecules – fats – rather than proteins or DNA we have opened a new avenue to develop drug treatments for malaria.”

The team of researchers found that a molecule called gABCG2, which controls the transport of fat molecules, played a key role in this process.

“Female parasites build a deposit of fat in a localised spot, which is controlled by gABCG2,” Associate Professor Maier said.

“However, malaria genetically modified to have no gABCG2 did not accumulate fat in the same way, and crucially, struggled to survive in the mosquito.”

Dr Simon Brown, research fellow at UOW's School of Medicine and the Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute based, said the discovery could lead to new malaria drugs and even a vaccine.

"We are currently determining which specific fats are important for the survival of the female parasite with the aim of identifying the most appropriate target for future therapeutics."

The research team included scientists from UOW, the Australian National University, University of Melbourne and the Max-Planck-Institute in Berlin.

Media contact: Elise Pitt, UOW Media & PR Officer, +61 2 4221 3079, +61 422 959 953, epitt@uow.edu.au or ANU media office, +61 2 6125 7979.