October 20, 2022

First-ever genetic analysis of a Neanderthal family paints a fascinating picture of a close-knit community

For the first time, we have a glimpse at family ties in a community of our closest evolutionary relatives

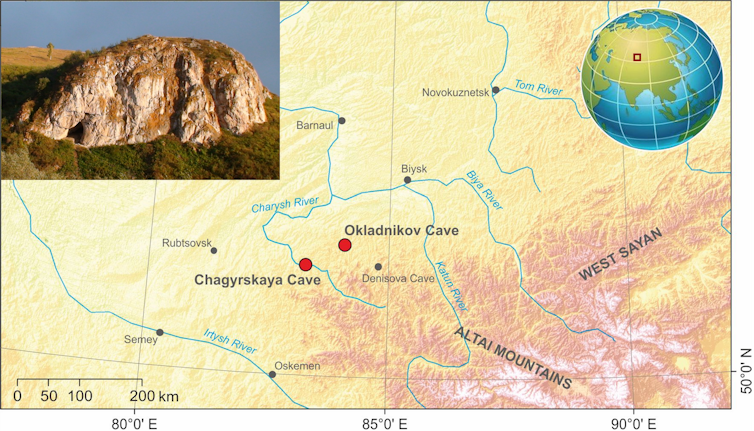

Our closest evolutionary relatives, the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), were once spread across Europe and as far east as the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia.

Yet more than 160 years since the first Neanderthal fossils were unearthed in Europe, little is known about the group size or social organisation of Neanderthal communities.

Using ancient DNA, a new study provides a snapshot of a Neanderthal community frozen in time.

With our colleagues, we show a group of Neanderthals living in the Altai foothills around 54,000 years ago consisted of perhaps 10 to 20 individuals. Many of them were closely related – including a father and his young daughter.

The easternmost Neanderthals

The first genetic clues to Neanderthals were obtained 25 years ago from a fragment of mitochondrial DNA, which is found in cell structures called mitochondria rather than in the cell nucleus.

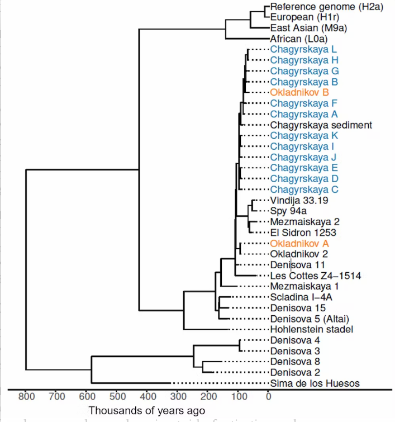

Subsequent mitochondrial DNA studies and genome-wide nuclear data from 18 individuals have sketched the broad brushstrokes of Neanderthal history, revealing the existence of many genetically distinct groups between about 430,000 and 40,000 years ago.

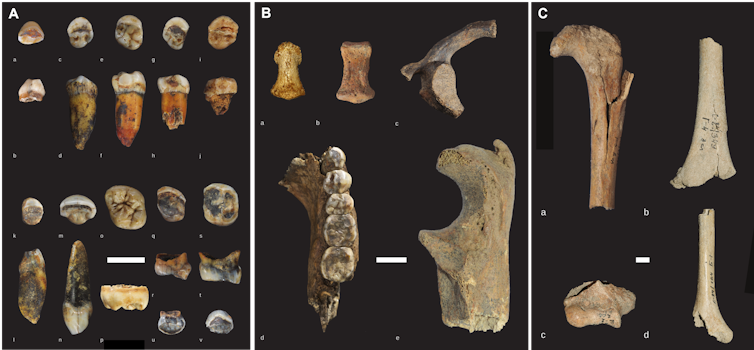

Our new study is the first to analyse ancient DNA from the teeth and bones of multiple Neanderthals who lived at around the same time. The fossils came from archaeological excavations of Okladnikov Cave in the mid-1980s and Chagyrskaya Cave since 2007.

These caves were used by Neanderthals as hunting camps. The remains of animals such as bison and horses are abundant, and more than 80 Neanderthal fossils were also found in Chagyrskaya Cave – one of the largest such collections anywhere in the world.

Both sites also contain distinctive stone tools that bear a striking resemblance to artefacts found at Neanderthal sites in central and eastern Europe.

Family ties

To paint a detailed picture of the genetic makeup and relatedness of these Neanderthals, we analysed mitochondrial DNA (which is passed down the female line), Y-chromosomes (passed from father to son) and genome-wide data (inherited from both parents) for 17 Neanderthal fossils – the most ever sequenced in a single study.

The teeth and bones came from 13 individuals: 11 from Chagyrskaya Cave and two from Okladnikov Cave. Seven of the Neanderthals were male and six were female. Eight were adults and five were children or adolescents.

Among them were the remains of a Neanderthal father and his teenage daughter, as well as a pair of second-degree relatives – a young boy and an adult female, perhaps his cousin, aunt or grandmother.

Although the nearby site of Denisova Cave was inhabited by Neanderthals from as early as 200,000 years ago, the Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Neanderthals are more closely related to European Neanderthals than to the earlier ones at Denisova Cave.

This finding is consistent with a previous genomic study of a Chagyrskaya Neanderthal and the presence of distinctive stone tools at Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves that closely resemble those found at Neanderthal sites in Europe.

We also found the Chagyrskaya Neanderthals share several heteroplasmies – a special kind of mitochondrial DNA variant that typically persists for less than three generations.

Taken together with the evidence for their close family connections, these indicate the Chagyrskaya Neanderthals must have lived – and died – at around the same time.

On the brink of extinction

Our analyses also revealed this Neanderthal community had extremely low genetic diversity – consistent with a group size of just 10 to 20 people.

This is much smaller than the genetic diversity recorded for any ancient or present-day human community, and is more like that found among endangered species at risk of extinction, such as mountain gorillas.

The Chagyrskaya Neanderthals were not a community of hermits, however. We discovered their mitochondrial DNA diversity was much higher than their Y-chromosome diversity, which can be explained by the predominance of female (rather than male) migration between Neanderthal communities.

Did these migrations involve Denisovans, who occupied Denisova Cave repeatedly from at least 250,000 years ago to around 50,000 years ago?

Denisovans are a sister group to Neanderthals and they interbred at least once. This happened around 100,000 years ago, producing a daughter from a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

Yet even though Denisovans were present at Denisova Cave at around the same time as the Neanderthals living at Chagyrskaya and Okladnikov Caves, we found no evidence for Denisovan gene flow into these Neanderthals in the 20,000 years leading up to their demise.

Kindred spirits

In recent years, multiple lines of evidence have shown Neanderthals possessed technical skills, cognitive capabilities and symbolic behaviours as impressive as those of our ancient Homo sapiens ancestors.

Our genetic insights add a new social dimension to this picture. They provide a rare glimpse into the close-knit family structure of a Neanderthal community eking out an existence on the eastern frontier of their geographic range, close to the time when their species finally died out.![]()

Laurits Skov, Postdoctoral research associate, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Richard 'Bert' Roberts, Director, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH), University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

UOW academics exercise academic freedom by providing expert commentary, opinion and analysis on a range of ongoing social issues and current affairs. This expert commentary reflects the views of those individual academics and does not necessarily reflect the views or policy positions of the University of Wollongong.