Why are we so nostalgic for the 1990s?

Everything old is new again: that is a defining feature of pop culture.

December 12, 2019

The past few years have seen a surprising love for the 1990s – fuelled by our new methods of consuming content – that has infiltrated all areas of our culture and shows little signs of abating.

When I moved from the 1990s into the 2000s, I put my denim shirt and skinny legs jeans in the back of the cupboard, the old records in the garage, and the video cassettes in the bin. Now I wish I hadn't. My old clothes are now considered 'vintage', I could be making an extra income from my vinyl collection, and those dusty magnetic video box sets are once again all the rage.

Pop culture used to define a generation, but it seems the cultural, music and fashion trends of the 1990s have been recycled, and what Generation X considered its rite of passage into adulthood, is being discovered and claimed by fledgling grown-ups as their own.

There's been the resurgence of vinyl as the trend-setters' choice of music consumption rather than the ease of a digital download, and now the hipsters have discovered the nostalgic sound of a whirring cassette from which to enjoy the dulcet tones of everyone from Salt-N-Pepa to Rick Astley.

Dr Renee Middlemost, a Lecturer in Global Communication and Media in the University of Wollongong's Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, says the sense of nostalgia that seems to be gripping Generation Z is influenced, paradoxically, by the huge amount of pop culture content with which they are faced.

"Every generation looks back at past trends," says Dr Middlemost, an expert in pop culture.

"My background is cult cinema and there has been a lot done around nostalgia in cult cinema and what people become nostalgic for, even things that were not around when they were born. It is an interesting thing that is happening now and I have seen it in my students who are all into watching shows like Friends.

"I believe it has something to do with the way people are watching media these days. With platforms like Netflix around, people recommend shows to each other, and there are less people seeking out new things. Our tastes seem to have narrowed.

"The whole sharing thing with Netflix and recommendations that has narrowed the tastes of people in regards to television viewing has been seen in cult cinema, too. It's all been done by word-of-mouth. And with the sharing of videos and content, the online world has made the pop culture loops come around much more quickly than before."

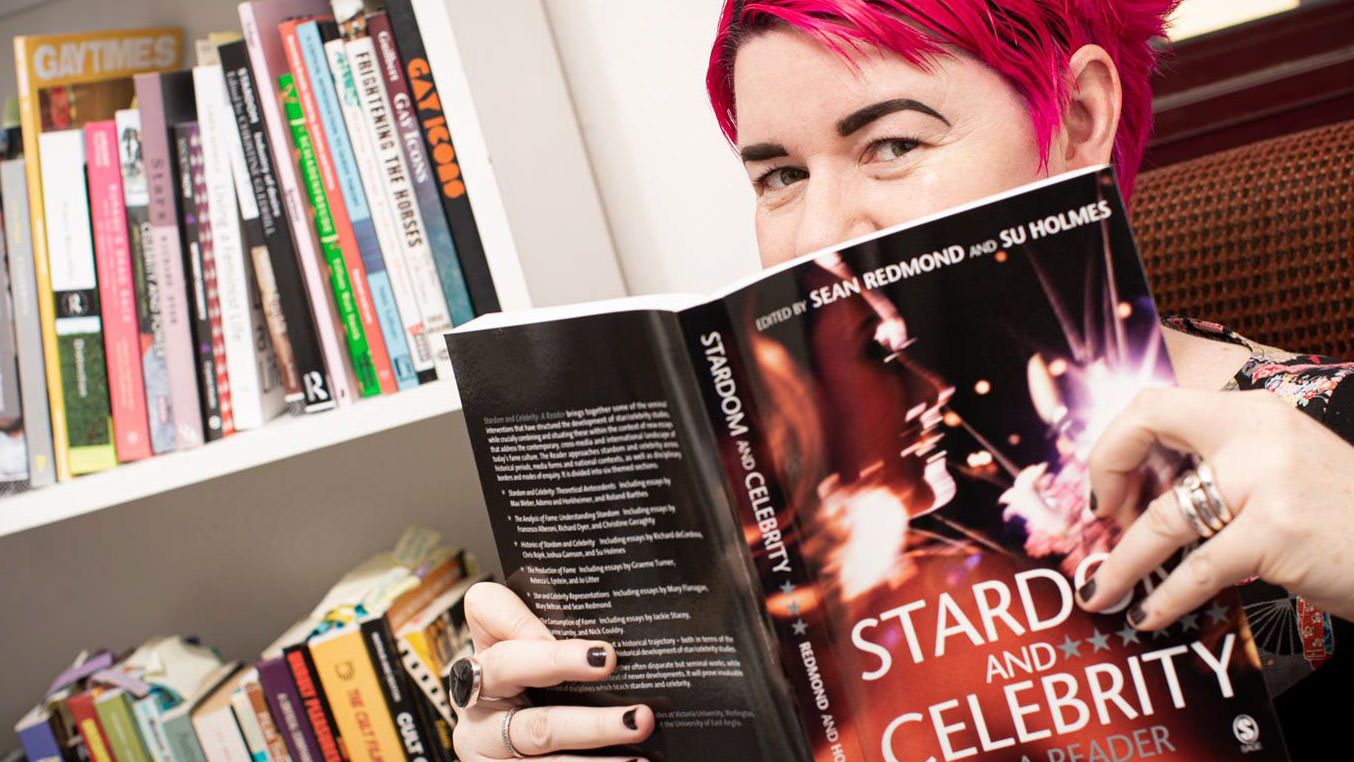

Dr Renee Middlemost, an expert in pop culture and cult cinema at UOW.

Nineties nostalgia is pervasive in nearly all entertainment- from cinema, to TV, music and fashion, and although reminiscing about the good old days is not new, it seems the passion that '90s pop culture elicits is.

That obsession with the last decade of the last Millennium was highlighted in the recent collaboration by Millennial maestros Charli XCX and Australia's own Troye Sivan in their collaboration 1999.

The pair hark back to the days of daggy, singing 'I just wanna go back, back to 1999/Take a ride to my old neighbourhood/ I just wanna go back, sing: 'hit me, baby, one more time', All while dressing up as Kate and Leo in the iconic Titanic scene (from 1997) on the ship's bow and celebrating the leather-clad hero Neo of The Matrix while working on their iMac desktop computer.

There's no denying the love for all things 1990s in 2019 but why it is so entrenched in the lives of those who have grown up with information at their fingertips and phones that are for everything except calling close friends?

Looking back to the last generation 25 years ago, that seems to be true. Back then, the Beastie Boys were singing about cop shows of the 1970s and the silver screen was hawking remakes of classics like The Fugitive and The Saint.

However, there are other theories about why '90s pop culture has come of age once again. Arguably, the 1990s produced some of the best - or at least, the most influential - television, music, and movies. Indeed, many movie critics have made the case that 1999 was the best year ever for movies, featuring high-quality films that have become part of the cultural dialogue.

The 1990s were a unique period in modern history in terms of technology and social connection. At the start of that decade, mobile phones were for the rich and famous and did nothing but make and receive calls. The internet hadn't been invented, google was a made-up word, and social media was meeting your mates at the Hoyts theatre complex to roll Maltesers down the aisle.

By New Year's Eve 1999, the first dot-com collapse was on the brink of occurring and our lives had become mobile and connected in ways the Baby Boomers could never have imagined.

"Why the internet generation wants to watch reruns of Friends and Seinfeld I think goes back to the nostalgia of things - when you're feeling dark about the world you go back to the things that make you feel better," says Dr Middlemost.

"There will be some event on Twitter like the Christchurch massacre and you want to go back to watching something that can help get you through that dark period. It's not always nostalgic things but it is things that make you feel good.

"These shows are the ones today's Millennials were watching when they were growing up, or what their parents were watching."

And although the substance of these '90s classics may be dated in many ways, they still contain universal themes to which young people can relate, says Dr Middlemost.

"There are enough similarities in those shows that the younger generation can relate to even if it is not identical to their own experience. If you look at Friends you can see why young people are interested in that - you always want to hang on to your friends. It's also a show about negotiating life in your early 20s. If you watched the show the first time around you would see how it would be dated, but those common themes continue to be popular."

While our screens are becoming saturated with sitcoms from the '90s, our AirPods are being filled with sounds from the Spice Girls, Nirvana, and Oasis.

Liam Gallagher, lead singer of Oasis, is headlining this year's Fairgrounds Festival at Berry in early December. While the rest of the line-up includes some of the current crop of crooners, it's Gallagher the young and the not-so-young are splashing out up to $250 per ticket to see.

Dr Tim Byron, from the School of Psychology at UOW, says there is always a part of pop culture that is focussed on the past, especially in music.

"It's all about contextualising and putting music into new combinations, that is how pop culture grows," says Dr Byron, whose research is focused on the connection between music and memory.

"The distinctions that made the music part of a certain era don't matter because the people who are now listening to it don't care. They weren't born when the original song came out."

Music can be intergenerational, he adds.

"One of the interesting things about music is that young people are not only listening to things their parents listened to but also their grandparents. There is something fascinating about the ways in which young people interact with pop culture songs.

"One of those things is that the distinction between the eras don't matter to them - it's all old. They will go to a dress up party and mix up their eras. Any bit of pop culture has a meaning for certain people that is different to those who were around at the time that culture was happening.

"What's going on is that when new people come along and find new meanings to music or any pop culture it challenges people, depending on how much of their personality is tied up in that era and those memories."

Dr Tim Byron, from UOW's School of Psychology, says pop culture often repeats itself.

Just like accessibility has changed the way in which the later generations watch media content, streaming services have also changed the way in which they listen to music, and the revival of '90s melodies.

"Bingeing has changed the way we consume and interact with pop culture, and it has certainly changed the way people consume music," Dr Byron says.

"The equivalent in music is streaming services like Spotify. You can search and listen now to whatever you want, and listen to your heart's content. You don't have to buy the CD anymore, and that has changed what people listen to as well, for obvious reasons."

With less cost entry, listeners can get to the strange and weird stuff quicker, says Dr Byron.

"It democratises music. Young people may still get peer-pressured into listening to what their friends want them to listen to, but the other stuff is also easy to find. In the '90s, original music was harder to find and harder to purchase, and a lot of the time those sold in music stores were covers. Now it's originals on streaming services, not covers."

With the end of another decade fast approaching, the next cycle - or recycle - of pop culture could be about to be change. Instead of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Britney Spears and double-denim and high-waisted mum jeans, we'll be listening to Gwen Stefani, wearing metallic tank tops and bingeing on The Sopranos.

Feature illustration by Kate Powell