Footballs, meat pies, kangaroos and… vaccinations?

How iconic ads are making a comeback with the promise of a COVID-free future.

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent vaccination rollout has caused advertisers to pivot from traditional messaging. Brands are letting their products take a backseat and instead promoting connection with their consumers through one shared goal: a COVID-free future.

Dr Jennifer Algie is Senior Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Wollongong (UOW) with a focus on social marketing and individual behaviour choices of consumers.

“Social marketing looks at behaviour change. It’s about individuals bettering society and doing things for the greater good, such as promoting blood donation. We’re seeing that in vaccine marketing – the goal is not just to protect the individual, but broader than that, protect others in society,” says Dr Algie.

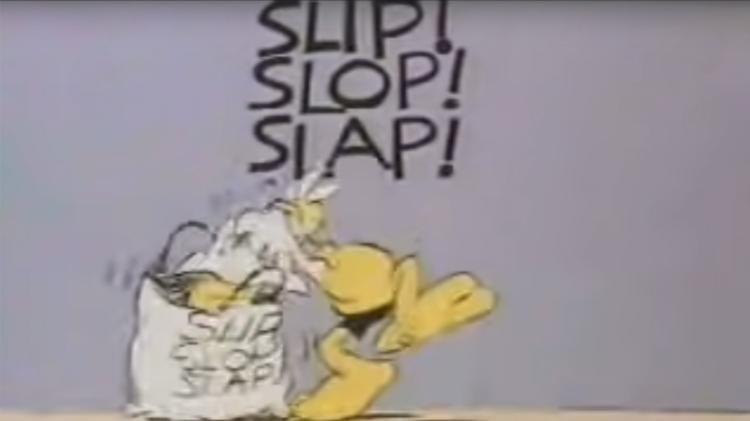

The 1980s saw a boom in memorable social campaigns in Australia, such as ‘Slip, Slop, Slap’ and ‘Click Clack, Front and Back’. Dr Algie says that few campaigns have kept up that momentum in recent times.

The Slip, Slop, Slap ad has continued to evolve since it first aired in 1980.

“There isn’t that continuity in social marketing programs anymore, they don’t build up brand awareness in taglines. Being able to pinpoint a really good recent social program, we’re not seeing the longevity” she says.

The Australian Government faced public backlash for its original vaccine campaign, which saw a young woman gasping for air on a ventilator. Dr Algie says while fear-based campaigns are effective, this was the wrong approach.

“They initially wanted us to go and get vaccinated, but there wasn’t the supply there. Firstly, there should have been a good proposition, offering value to your citizen or community member. It should be making access to do the behaviour easy, and then addressing the pricing of it. It’s not a monetary price but looking at costs of doing this behaviour. If people have hesitancy about being vaccinated, what are some ways of reducing those costs or those barriers to making the behaviour change?” she says.

The government ad depicted a young woman gasping for air, despite many people her age being ineligible for vaccines at the time.

Campaigns from around the world have employed a more positive and emotional angle, which has seen corporations follow suit.

QANTAS released a tear-jerking commercial showing individuals getting vaccinated and telling the nurse where they were travelling once immunised, while VB used archival footage telling us to “earn a thirst” by getting the jab.

Chewing gum brand Extra showed the heart-warming, and hilarious, release from lockdown to the backdrop of Celine Dion’s ‘It’s All Coming Back to Me Now’, reminding consumers to have fresh breath before reuniting with their loved ones.

Even AAMI’s Rhonda and Ketut returned after almost ten years, via video call, telling us to get vaccinated so we could meet their fictional baby.

Consumers followed Rhonda and Ketut’s love story over a series of AAMI ads, now they’re back with a message to get vaccinated.

Dr Algie says that the vaccine campaign is potentially the first instance in which private corporations are promoting public health messaging to their consumers.

“Companies often shy away from things that are too controversial, but it’s in these companies’ best interests to get people vaccinated. You can see why VB wants people back in bars, drinking their beer, and why QANTAS wants people back on planes,” she says.

“Health promotion doesn’t get a lot of money thrown behind it, so the more we have industry buying in, manufacturers and the business sector, that’s more exposure for vaccination. There was another government ad with a health expert walking towards the camera, which didn’t have the emotional element. I think it’s great that brands have this opportunity to form a connection with their audiences, and they will have done their research into their audiences.”

What makes a good social marketing campaign?

Dr Algie, whose past research has focused on road safety campaigns, says advertisers need to aim at changing society’s acceptance of behaviours to be effective.

“The Transport Accident Commission (Victoria’s road safety authority) is very well known for the ‘if you drink, then drive, you’re a bloody idiot’ campaign. That really focused on shifting social norms, making it very undesirable, saying you’d be a social outcast if you are caught drink driving,” she says.

The ad, which originally aired in 1989, showed realistic-style footage of a woman being rushed to hospital after a drink driving accident, and the subsequent conversations between doctors and her parents.

Historically, fear-based campaigns have been effective. The infamous ‘Grim Reaper’ AIDS campaign, which aired for less than a month in 1987, faced criticism for its alarmism, but is still considered one of the most effective public health campaigns of all time.

Dr Algie says there are ways to effectively execute these types of advertisements.

“What I’ve found from my research in road safety is you need to spend the latter part of the advertisement really calming people down, showing them that it's an easy behaviour to do, and showing them the benefits,” she says.

“I disagreed with that vaccine ad [of the woman on the ventilator] when it was first running because the supply was not there. It's not fair to make people feel really anxious and then not let them do anything about it. Whereas now I think you could go for it. You could make vaccine contemplators feel anxious. Then I would be emphasizing at the end, all of the information about how and where you can go and get vaccinated.”

As with any advertising campaign, Dr Algie says understanding the attitudes, ideas and behaviours of your target market is key.

Recent government campaigns have publicly missed the mark. In April 2021, the ‘Milkshake Video’ was condemned by education and consent experts, and eventually pulled from its platform, for its confusing metaphors and misinformation.

In 2015, the 'stoner sloth' campaign, aimed at highlighting the dangers of cannabis, became an accidental meme. The ads were commissioned by the NSW government for $500,000, but instead of turning teenagers off marijuana, became a joke amongst the smoking community. The campaign even drove audiences to a Colorado-based cannabis store of the same name.

“That’s the perfect example of a marketing or advertising agency not testing its messaging. If they'd even tested that with a handful of people, they would have realised that it would be seen as very comical through the eyes of their target audience,” says Dr Algie.

“I think the way forward with getting more people vaccinated is understanding and segmenting your market. The VB ad was great, it's not preaching to the converted, but it's just reinforcing people's feelings. One good thing about these companies doing this advertising is that pressure on social norm – it’s the norm now to be vaccinated, and that does put pressure on that smaller percentage of the population who are reluctant.”

VB is one of the latest brands to entice its consumers to get vaccinated.

Social marketing in the streaming era

Dr Algie says with the expansion of streaming services and internet use, governments and brands alike must rethink their approach when it comes to advertising for the greater good.

Rates of free-to-air viewing are on the decline, meaning traditional television campaigns may no longer have their desired effect.

“There is a big shift of younger people only accessing content through streaming services, while your baby boomers and over-75s are the only ones left watching free-to-air. It's much more difficult now to generate public awareness of a health message because we're not tuning in,” says Dr Algie.

She says this shift provides industry with more opportunity to align their brands with a pro-vaccination message, by using their products to incentivise people to get the jab.

Northern Territory Tourism has offered $1,000 discounts for fully vaccinated travellers, while Australian music giants Live Nation, Frontier Touring and TEG are offering free concert tickets to double-jabbed patrons as part of their Vax-stage Pass competition.

“An effective technique here is self-re-evaluation, which is about making people question their identity. Getting people to think that they're no longer happy being unvaccinated and that they'd be happier being vaccinated – realising that you can get invited to picnics, you can have children over to your house, you can eventually go out and dine in restaurants. It’s making your vaccination status become part of your identity.”

At time of writing, COVID-19 vaccinations are currently available at GPs and pharmacies, including the UOW Wollongong Campus Pharmacy, as well as the Mass Vaccination Centre in the Wollongong CBD.