Fifty shades of green

The good and the bad of cannabis go hand in hand

November 24, 2017

Celebrated for its medicinal properties but recognised as a trigger for mental illness.

Marijuana, pot, ganja, grass, hashish, weed, Mary Jane - for all the names that we have for cannabis, there are hundreds more chemical compounds that make up this alluring plant.

New research showing that cannabidiol, a non-intoxicating component of cannabis, may alleviate symptoms of schizophrenia not addressed by current medication has once again thrown the spotlight on the medical use of the plant.

Likewise, legislation around patient access to medicinal cannabis is changing rapidly in Australia, while the $2.5 million federally funded Australian Centre for Cannabinoid Clinical and Research Excellence (ACRE) is set to steer future research and national policy.

This is a critical time to understand the disparate effects of cannabis in the brain and establish clear guidelines for its medicinal use.

Australia has one of the highest rates of cannabis use the world over and cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in the country.

Some people dabble in recreational cannabis but others depend on it daily. There is a spectrum of recreational cannabis use - and with that, a broad range of adverse effects that includes, most seriously, psychotic episodes and illness.

On the other hand, medicinally, there are high hopes for cannabis. It can relieve chronic pain, nausea and vomiting, daily seizures and muscles spasms in late-stage cancer patients or those undergoing chemotherapy, children with certain forms of epilepsy and adults with multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as other debilitating conditions.

Touted as a natural wonder drug, cannabis can ease an array of symptoms. This is because cannabinoid receptors, the receivers for cannabinoid compounds on the outside of our cells, are found throughout the entire brain and body.

Professor Nadia Solowij, Co-Director of ACRE and Head of Research in UOW's School of Psychology, has been investigating how cannabis alters the brain for 25 years, fascinated by how drugs affect people so differently. She has conducted brain-imaging studies with different cannabis users, from adolescents experimenting with cannabis through to daily users of more than 20 years, mapping the changes in their brains.

With decades of research in mind, she makes two points: "There is this huge variability in how cannabis affects people and then also its association with schizophrenia."

Heavy and prolonged recreational cannabis use affects verbal learning, attention and memory - brain functions that are collectively termed cognition. It also affects executive functions like planning, reasoning and problem solving. "These cognitive impairments are characteristic of people with schizophrenia," Nadia says.

In her research, Nadia found some recreational cannabis users are impaired on a range of levels - cognitively, socially, psychosocially - and yet others seem to be able to smoke daily while remaining high-functioning individuals. When it comes to cannabis, not all brains respond the same.

Professor Nadia Solowij has been investigating how cannabis alters the brain for 25 years. Photo: Paul Jones

Cannabis and schizophrenia

The brain is particularly sensitive to the effects of cannabis during adolescence, a prime period of neurodevelopment. The younger people start smoking cannabis, and the more frequently they do so, the greater the risk and severity of lasting adverse effects. For some people, cannabis targets and amplifies an underlying vulnerability towards schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is an illness that disrupts regular brain function and causes intense episodes of psychosis. Hallucinations and paranoia spring from a distorted perception of reality. Other symptoms include lack of motivation, social withdrawal and impaired cognition. Cannabis use is a risk factor for schizophrenia, the drug affecting the same brain regions and systems that are disrupted in schizophrenia.

"It has never been my mission to prove that cannabis is really bad," says Nadia, who is often labelled as anti-cannabis, most of her research describing the harmful effects of chronic use of the drug. "I've just been trying to understand it."

More recently, Nadia has been shedding light on the medicinal properties of cannabidiol (CBD), a non-intoxicating compound in the plant. She has compared its effects to tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive component, better known as THC - "the one that gets you high and is responsible for cognitive impairment, as well as structural and functional changes in the brain".

Promisingly, CBD has shown neuroprotective properties, reduced psychological symptoms and improved cognition in cannabis users, even increasing the size of certain brain regions involved in memory function after 10 weeks of treatment with CBD. This work has involved PhD student Camilla Beale.

Before delving deeper, it's important to understand that specific cannabinoids have distinct effects on mental health and brain function. As it is recreationally used, the cannabis plant is a potent mix of chemicals and THC is the main culprit of psychotic effects.

The THC content varies greatly in street cannabis but overshadows all other compounds. Studies of therapeutic CBD generally administer an isolated compound, distilling the positive effects of CBD from the whole plant, or use a CBD-enriched extract.

"I'm not driven by the medical marijuana push," Nadia says, "but by what are really exciting findings in this area of research."

New territory for cannabinoids

Chemicals in our brain, including ones we produce as well as drugs we introduce, feed into a complex web of messages sent and received, instructions for our brain and body to work. As we learn more about the intricacies of the brain, new therapeutic avenues appear.

Dr Katrina Green is a neuroscientist who has focused on understanding how antipsychotic drugs, like those prescribed to treat schizophrenia, act on the brain and cause heavy side effects in some people.

Current antipsychotic drugs target the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, the highs and the lows, but do little to address cognitive impairments; they also carry the risk of weight gain and diabetes. These limitations have driven Katrina to research new therapeutic approaches.

Recently, Katrina has found herself on the front line of debate about medicinal cannabis. She published some encouraging results earlier this year, a collaboration with Nadia and PhD student Ashleigh Osborne, that showed CBD has therapeutic effects in an animal model of schizophrenia, alleviating cognitive impairment.

In their study, CBD restored recognition and working memory, as well as social interaction, to normal levels - without any side effects of weight gain. "My research group is suddenly in a position to lead this work and we have to get it right," Katrina says.

More work needs to be done to see if these cognitive findings translate to people with schizophrenia but there are promising preclinical results for using CBD in other conditions associated with cognitive impairment, like Alzheimer's disease and stroke.

Dr Katrina Green's team is leading research into how antipsychotic drugs act on the brain. Photo: Paul Jones

What we don't know yet

Cannabis plays into the endocannabinoid system, named and famed for the drug that led to its discovery, but we don't yet know the full scope of this system.

When it was first identified, the endocannabinoid system was a two-part assembly that explained how THC causes its intoxicating effects. In the brain, THC found its matching receptor. "They called it the cannabinoid (CB1) receptor and it was thought to be solely located in very specific regions of the brain," Katrina explains.

Now we know the system is located throughout the body, on cells of our immune system, and everywhere in the brain. Our bodies also produce their own cannabinoid compounds as part of normal functioning.

Our understanding is being rewritten each year as new parts and players of the endocannabinoid system are discovered, their interplay better understood. "An author called Vincenzo Di Marzo puts out a review almost every year - and every year it changes," Katrina says.

"We don't have these receptors in our brain so that we can smoke cannabis," she continues, "so what is that machinery there for? It's for normal brain functioning." The endocannabinoid system regulates neurotransmitters, like dopamine and serotonin, key messenger molecules in our brain that are implicated in basic human functions like thought processing and emotions, but pathologically in addiction, depression and psychosis.

It also modulates cognition. Introducing a foreign chemical into that finely-tuned system can disrupt the balance in the brain.

"There needs to be a level of caution with medicinal cannabis as there are so many unknowns. We're still working in the dark because we don't know entirely what is in the cannabis plant and we don't know the extent of the endocannabinoid system," Katrina says. "But that's also exciting because the potential is endless."

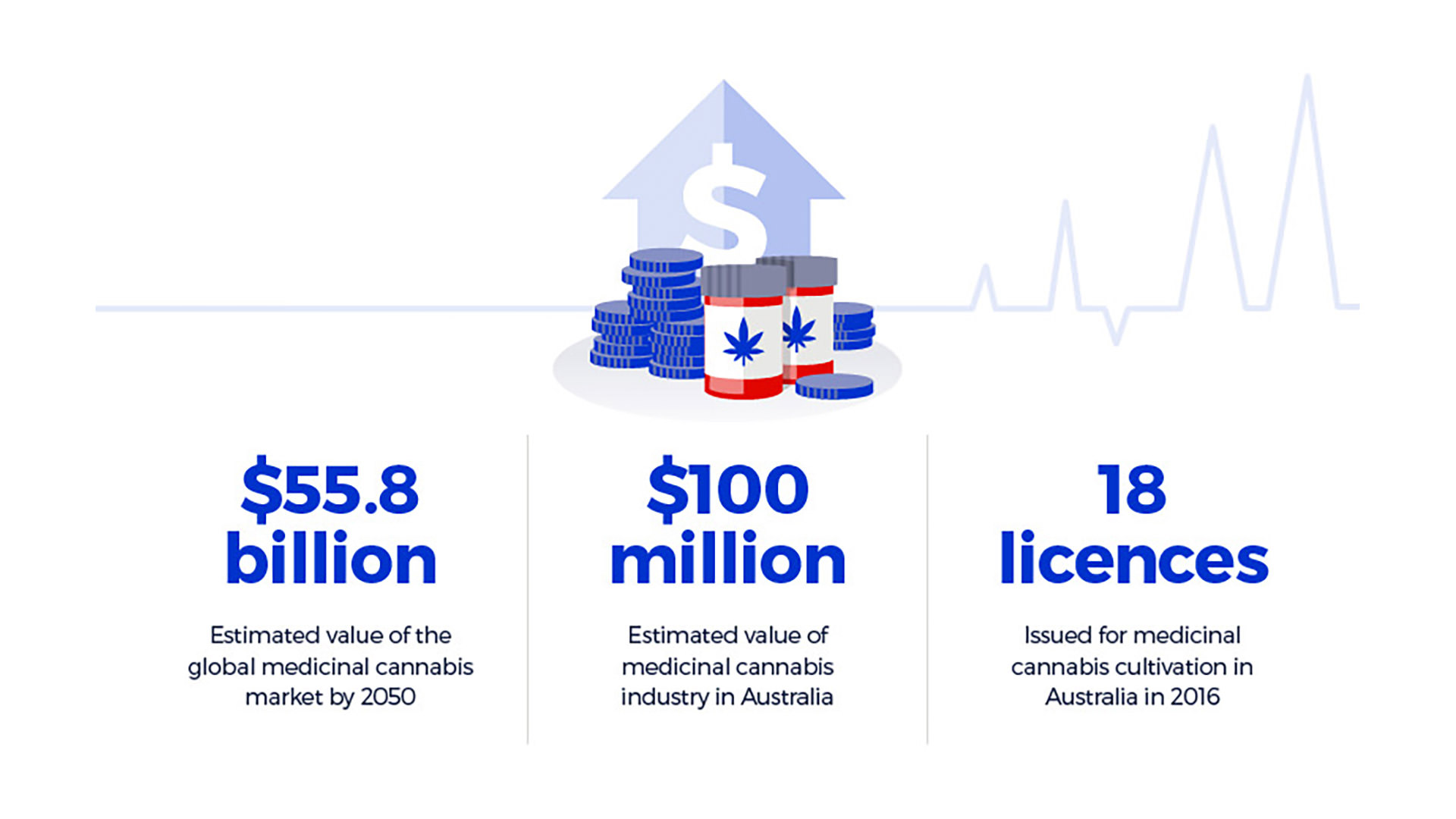

Medicinal cannabis in numbers: industry

The economic case

The evidence for the therapeutic benefits of CBD is mounting but far from definitive. Meanwhile, the quest for new antipsychotic drugs that treat schizophrenia without severe side effects is also reaching a crisis point. Nadia and Katrina's work is pivotal, now more than ever, informing policy decisions and future research.

A long time coming for some, policy around the legalisation of medicinal cannabis in Australia is shifting rapidly - sometimes back and forth with debate. Made legal for medicinal use in 2016, federal laws regulate the importation and local cultivation of cannabis but states and territories are making their own decisions about how doctors can prescribe medicinal cannabis products and for whom.

It was first legalised in Victoria for children with severe epilepsy; other states are waiting on the outcomes of clinical trials.

Medicinal cannabis in numbers: patients

Professor Simon Eckermann, a health economist at UOW's Sydney Business School, is interested in optimising the net benefit of medicinal cannabis. He takes the cost of cultivating cannabis varieties for specific populations into account relative to current health practice. He says the benefit of medicinal cannabis for certain patients is clear.

"There is conclusive evidence for using medicinal cannabis for chronic pain, principally cancer and neuropathic pain, to relieve nausea and vomiting for patients undertaking chemotherapy and in MS populations for spasticity, chronically ill and palliative populations," Simon says, citing the most comprehensive review of medicinal cannabis evidence to date undertaken by the US National Academy of Sciences.

"Compassionate access for selected patient populations is justified in Australia now, as in other countries."

Significant downstream hospital cost savings could be made by using medicinal cannabis as an alternative pain relief for people with chronic pain or in palliative care, considering Australia's ageing population (see infographic). Varieties of cannabis rich in CBD, THC and aromatic terpenes have twice the impact of opioids like morphine and codeine for severe pain relief in cancer.

Professor Simon Eckermann says the benefit of medicinal cannabis for certain patients is clear. Photo: Paul Jones

Where to next for medicinal cannabis?

Currently, patients in Australia with debilitating illnesses can access medicinal cannabis by participating in clinical trials or through compassionate access schemes where their doctor must seek approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Most recently, changes were made to restore fast-tracked access for terminally-ill patients.

These legislative changes have caught the medical community unprepared. Supply of safe, quality product is also a hurdle. "There have been no guidelines about what doctors should prescribe, at what dose or for what indications," Nadia says. "Most patients are resorting to illicit products because there is no good quality product in Australia and because there are so many hoops to jump through to access it."

Katrina weighs up the issues on both sides: the red tape delays that prohibit people from accessing cannabis products and the liability of prescribing doctors. "You don't want to be restricting access to particularly ill people who are benefiting from this but there needs to be clear definition that like any medicine it has its prescribed uses."

Announced in October, this is the goal of ACRE: to enable doctors to deliver evidence-based practice by consolidating existing data and linking health outcomes of current medicinal cannabis users with further research. Research will cover cultivation under good manufacturing practice through to clinical trials. The centre is co-led by Nadia and her University of Newcastle colleague Professor Jenny Martin.

"We have the opportunity to get it right at this critical time in Australia," Nadia says. "We could lead the world in the implementation of safe medicinal cannabis products with an underlying base of science and research - but it takes time."

Marijuana, pot, ganja, grass, hashish, weed, Mary Jane - for all the names that we have for cannabis, there are hundreds more chemical compounds that make up this alluring plant.